In the Diversity and Inclusion world, we talk about the “business case” for D&I programs as a way, in part, to convince people that sitting through sessions where they have to dig deep into sometimes uncomfortable topics such as self-understanding, bias, stereotyping, and inequity is worth it. To be fair, these sessions often ask a lot of participants – are they willing to look at their own biases, examine their cultural influences, be open to other’s stories, etc. The business case is about telling participants that this hard work pays off – in the work place environment and in the bottom line. But, are there limits to this approach?

Studies show that companies and organizations that focus on D&I strategies and initiatives have better employee engagement that can lead to greater innovation and ultimately, a bigger bottom line. We see examples of this everywhere.

- Employees that identify as LGBTQ who are ‘out’ at work are 20%-30% more productive than their closeted counterparts.

- The primary difference between women in tech who stay in their position or leave is their experience in the workplace.

- Multicultural women are almost 50% more likely to stay with their companies when given comparable opportunities if they feel they have male allies at the leadership level.

- Research shows that even more productive and innovative than monocultural teams are multicultural teams in which leaders acknowledge and affirm cultural differences.

I could go on. But, again, are there limits? Does our concern about revenue provide enough reason to do this work?

For most people, companies, organizations, school systems, or governments, the answer is no. We may begin by looking at the business case, but in the end, this work is about people. It is about equity and equitable systems. We don’t just need to have more inclusive workplaces so that more people are more productive; we need inclusive workplaces so that people can feel comfortable bringing their full selves to work and to the world.

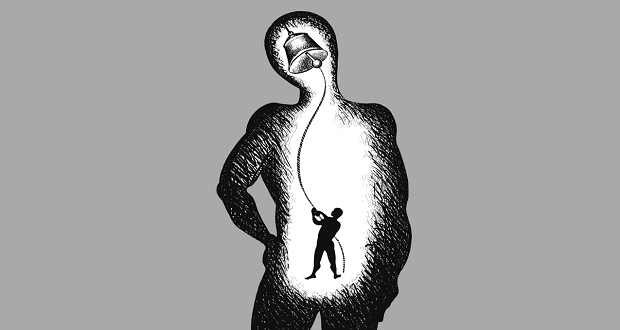

When we talk about social justice, another angle from which D&I is practiced, we often talk about dismantling unjust systems. At the root of this dismantling are the people who are willing to do the hard self-work. When we begin to encourage people to be fully who they are, and when we begin to build relationships across difference, we begin to dismantle systems that degrade and divide. We often can’t see injustice and inequity until we see and hear from people who are affected by it, and we all have our blind spots. Seeing people for who they are allows us to see what affects them, what moves them, what hurts them, and what makes them feel safe. Once we see those things, we can begin to build system that honor and protect those perspectives.

The trick is that these choices to dismantle inequitable systems and be people-centered may not always at the outset seem to be the best business decision. NFL teams choosing not to sign Colin Kaepernick — as well as the San Francisco 49ers who did not fight to keep him — surely think they are making the right business decision. In 2016, nearly one-third of NFL viewers who responded to a poll in Sporting News said they were less likely to watch games due to Colin Kaepernick and other player-led protests against racial injustice while only 13% of people were more likely to watch because of these protests. But, if we look past the bottom line, what does it mean in the long-term, culturally and in terms of profits, for a team—an organization—to dismiss a player’s rights to free speech? Do companies and organizations have a responsibility to their employees to respect their full selves, even when it’s uncomfortable or unpopular?

I was talking with a relative of mine who is the principal of an elementary school in the suburbs of Atlanta, and she shared a powerful story about the importance of inclusion efforts that go beyond the status quo of comfort and a “Let’s not rock the boat” mentality. A few weeks ago, a second-grade student in her school refused to stand for the Pledge of Allegiance in music class. While the teacher reacted emotionally from her own center of beliefs and shamed the student for being “disruptive”, my aunt took the time to understand the situation and asked the student to explain. He responded saying, “’Liberty and justice for all’ does not mean all.” This student is Black and his parents had been talking to him about his rights and equality, and he brought all of this with him to school, just wanting to express his full self. So, my aunt affirmed him, affirmed his parents, and communicated in no uncertain terms that this student has the right to sit or stand—has the right to be who he is—as long as he is not being truly disruptive.

I tell this story because I think it shows the importance of going beyond profit, beyond comfort, and beyond emotion. Think of how empowered this young student must feel and the leader he has the potential to become – in part because the person in power in the situation, whether it was his parents or his principal, listened and learned and respected. What is the long-term benefit of going beyond the bottom line? We will have leaders and employees who feel empowered and who are fully themselves and perhaps more accepting of others.

So, what are the limits of “bottom line D&I”? Maybe it’s not a limit as much as it is an invitation. Sometimes, to empower true leaders and to encourage and protect all voices, we have to look past our comfort levels and past what know to be profitable at the time. We have to look long term at who we want to be – as an organization, as a company, and as a society.