As a career educator, the conversation about gaps in educational achievement, particularly the disparity between underserved populations—children of color, poverty and with disabilities as compared to counterparts who are white, Asian, and from better socio-economic circumstances—always circles back to the notion of equity.

For years, we focused on being fair. Often in education, we tend to focus on standardization and compliance. The very notion of fairness, while closely related to concepts like equality or impartiality, assumes that students will have an equal opportunity regardless of their individual circumstances and will all benefit from the same provisions. This flawed notion does not account for the deficits that might prevent access to opportunities for one student that may not be a deficit for another. An assumption of sameness is the basis for this approach.

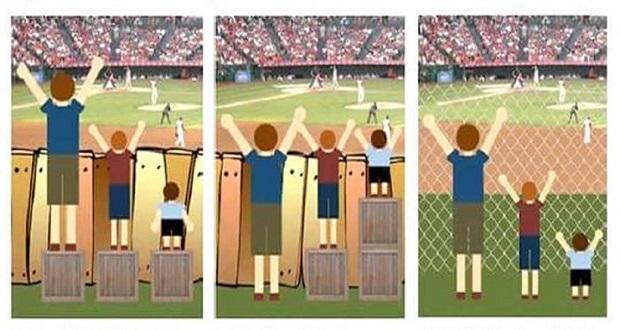

We see that in the first illustration above. Every child, regardless of their height, is provided with the same resource. The students all start at the same point and need the same help. It could be argued that it’s a fair approach, no child was given favor over another, and therefore they should be on equal footing and get the same end result. The assumed outcome is that fairness creates equality. Notice however, that said fairness still does not yield a result where every child is able to access the opportunity to see over the fence.

Equity in education requires that conditions are created that eliminate the obstacles to opportunities regardless of factors like race, gender, family background, language and poverty. The hard truth is that some students will need more. There are students who lack the necessary requisite skills to ‘do’ school by no fault of their own, due to circumstances out of their control.

Research tells us that the disparity by zip code alone means that students can be born into conditions that limit their access to pre-natal care, quality pre-school learning, libraries, good nutrition, high quality teachers, strong neighborhood schools, and after-school and summer enrichment activities. All of these factors create the conditions that manifest in poor academic performance and long-term impact on such things as access to rigorous courses, graduation rates, access to higher education and career readiness.

In the second illustration above, the supports are differentiated based on individual need, and those supports make it possible for each student to have the same vantage point, regardless of their individual heights. This is a more equitable solution.

But, let’s play this example out even further and consider a few additional constraints. In the second panel of the illustration, it can be safely assumed that the boxes were provisioned based on need. Here, it’s important to acknowledge the distinction between need versus deservedness, a distinction that is too often not made when discussing achievement gaps in the education system.

The term “deserve” is defined as:

to merit, be qualified for, or have a claim to (reward, assistance, etc.) because of actions, qualities, or situation.

“Need” is defined as:

circumstances in which something is necessary, required because it is essential.

A major barrier to equity in the education system is largely grounded in the beliefs of those who manage the system. Teachers and Leaders must firmly believe that creating equitable learning environments is a need, and not based on the myth of Meritocracy – distribution of resources according to merit, or by rewarding those who show talent, skill or demonstrate a work ethic. Meritocracy assumes that all the factors mentioned here – race, gender, language barriers and socio-economic disadvantage – don’t play a role in determining outcomes, but we know with certainty that they do.

In a recent discussion with educators, someone raised the following question: Why can’t all three of those kids just buy a ticket and get a seat in the baseball stadium like everyone else and not try to beat the system and watch the game for free?

This assertion assumes these students have the means to do so, or that they should just work harder to be able to have that level of access—that seeing the game should be based on their merit and work ethic. This response is tone deaf in that it negates the equity issue by suggesting a solution that puts the responsibility back on the students.

Inherent in the term “Achievement Gap” is the notion that the responsibility for achieving is on the student, and the gap is caused by their inability to perform. Instead, let’s consider the “Opportunity Gap,” which puts ownership in the hands of those charged with creating the learning and environmental opportunities for ALL students to be successful.

This brings us to the third panel of the illustration where the fence is now chain-linked and each of the children can see the game without any additional support. This represents a removal of the systemic barrier, which should be the ultimate goal in creating equitable systems of education.

Despite this, I offer an even greater challenge to contemplate. Is a fence necessary at all – whether chain linked or wood? What purpose does it serve? Have we built in systems of “gatekeeping” that we continue simply because we always have? What “gates”, both figurative and literal, are hindering our ability to lead and learn for equity? When we are able to explore the answers to those questions, we can truly get there, sitting at the ball game with ALL the students.