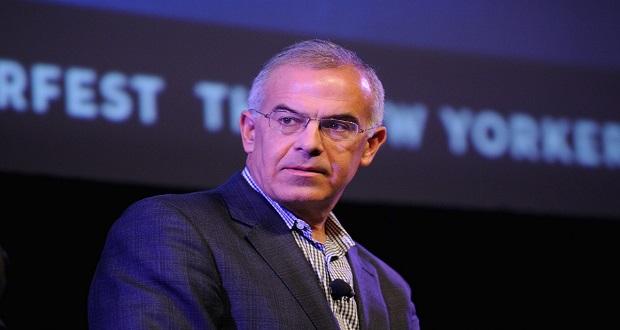

New York Times columnist, David Brooks, had the internet buzzing this week with his piece “How We Are Ruining America”, in which he argues that wealthy and upper class Americans perpetuate economic inequality with their status symbols of food, language, and commodities that become barriers to their poorer American neighbors.

The article starts off fair enough as Brooks references the structural differences that produce massive inequity in health, education, and housing across the social classes. But it’s when Brooks says, “I’ve come to think the structural barriers he (economist Richard Reeves) emphasizes are less important than the informal social barriers that segregate the lower 80 percent” that he derails into the typical individualism that defines so much of modern liberal discourse. In other words, Brooks privileges the individual over the social as the reason for inequity.

The next paragraph describes a recent lunch outing he had with a friend with just a high-school degree that he describes as indicative of the elitism at the root of inequity:

Suddenly I saw her face freeze up as she was confronted with sandwiches named “Padrino” and “Pomodoro” and ingredients like soppressata, capicollo and a striata baguette. I quickly asked her if she wanted to go somewhere else and she anxiously nodded yes and we ate Mexican.

As readers, we aren’t given any details about the nature or quality of their relationship or, more importantly, the perspective about the experience from Brook’s friend herself. But what is striking, and troublesome, is how Brooks discards all the material economic barriers that produced this interaction for the more palatable explanation that economic disparity comes from hard to pronounce sandwiches. I find his description of the outing, and his friends response, typical of the condescending and naïve outlook that is a natural product of having limited exposure and experience with different people —in this case, from a different social class.

Brooks’ description of his friend’s unease not only assumes that she is unaware and intimidated by these foreign sandwich options (as opposed to being uninterested or uncomfortable); but worse, he shifts the focus from the economic disparities that affect the ability to buy such sandwiches to the ability to pronounce or recognize them. In other words, the difference (and solution) between the rich and poor are the cultural symbols that divide—not the economic conditions that produce the materials in the first place.

Of course, having knowledge about dominant cultural norms has its place in surviving and overcoming inequities, but it is a small piece of the puzzle. The rest of the 100 pieces are the structural factors that shape the economic lives of individuals—and the sandwiches they can and cannot afford.

Sociologist, Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom, writes a much more complex and compelling piece on the double-edged sword of cultural capital. She highlights, through her own experiences as a professional black woman navigating upper class (white) spaces, the ways dominant cultural symbols are appropriated and employed by marginalized people to survive. But unlike Brooks, she acknowledges that becoming conversant with dominant discourse and cultural capital symbols (dress, food, language, codes) is a necessary evil and not the solution to equality. Writing about the stigma that many poor people must combat she writes,

You have no idea what you would do if you were poor until you are poor. And not intermittently poor or formerly not-poor, but born poor, expected to be poor and treated by bureaucracies, gatekeepers and well-meaning respectability authorities as inherently poor. Then, and only then, will you understand the relative value of a ridiculous status symbol to someone who intuits that they cannot afford to not have it.

I recommend you follow the link and read the whole piece for yourselves. But what strikes me is the acknowledgement that the “value of a ridiculous status symbol” pales in comparison to the economic conditions that make such code switching possible—and for many people, vital for survival. This is the double-edged sword of cultural capital. Especially so for marginalized people: you shouldn’t have to live with it; but you can’t live without it. Or at least until things change.