As a proud bookworm, I somehow always end up on the front doorsteps of any new bookstore or library. Needless to say, this past weekend in Brooklyn, I stumbled upon a small independent bookstore, full of typical indie bookstore things: the hot new fiction, memoirs by people’s favorite celebrities, locally made trinkets—the usual. However, there was a pleasant surprise in a part of the store that I typically don’t tend to peruse on the regular: the children’s book section.

This bookstore had a bountiful, colorful collection of children’s books that, from afar, looked like any other bookstore or library display. However, as I whisked by, I noticed something I hadn’t seen before: every book displayed featured racial/ethnic identities often underrepresented in literature: an African-American, Latinx, or Asian-American protagonist, navigating themes such as being a scientist, an engineer, or a creative. This didn’t stop at just fiction: the non-fiction children’s history books were all stories of powerful female leaders such as Frida Kahlo and Harriet Tubman. And no, they weren’t labeled “multicultural” or “diverse” children’s books. They were just “Children’s books.”

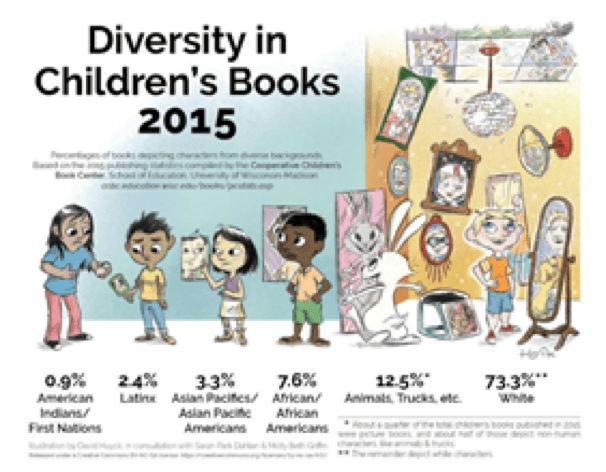

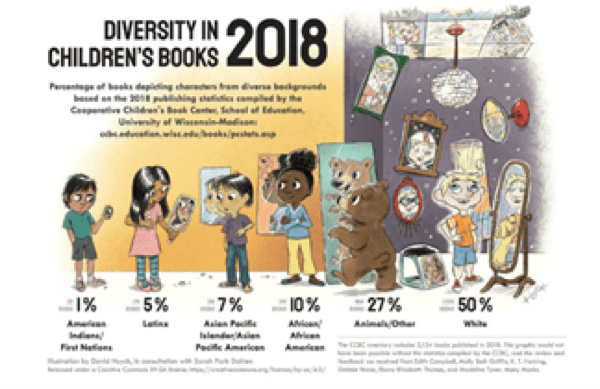

It turns out that, even just from 2015-2018, racial and ethnic diversity has come a long way in children’s literature. While there is much progress to be made, the pendulum is shifting.

I had to stop for a second and think of the books I had cherished growing up: Junie B. Jones, Ramona & Beezus, The Babysitters Club, and The Boxcar Children, just to name a few. I learned to love books at a young age; my mom had the opportunity to take my brother and me to the library weekly. There, as a creature of habit and a function of what I was exposed to in midwestern suburbia, I would either choose a book about white girls who go to school, play, and repeat, or a book involving animals. I loved them all and saw them as my world when, in reality, these stories were far from it. Did any literary “classic” I was assigned in grade school have non-white protagonists or families? And if they did, when were they not fleeing persecution (think Addy in American Girl books) or being ostracized because of their race (Claudia, an Asian character in The Babysitters Club)? Thus, finding books that represented my identities, particularly in a positive and empowering way, was (and still is) challenging and exhausting. Following the path of least resistance in book selection, especially in my youth, was inevitable.

Thus, finding books that represented my identities, particularly in a positive and empowering way, was (and still is) challenging and exhausting. Click To TweetWhat struck me most, however, was admitting to myself that I (and I’m sure many of you reading) still seem today to flock naturally to books featuring dominant narratives: stories focusing on middle-aged, upper-middle class white women who face millennial issues of money, relationships, and self-understanding. I do try to put in an active effort to read books by and about people of color. It has been only recently that I’ve been able to find authors names and storylines similar to my own reality.

In the diversity and inclusion space, we talk about how physical representation alone isn’t enough; this still remains true. However, it is important to realize how imperative representation is for children’s social and emotional growth and learning about inclusion. Diversity in children’s books is not just a response to a rise in socially-conscious parenting. Children themselves yearn to be represented: in Scholastic’s 2019 annual report, it is stated that regardless of their age, gender, or race/ethnicity, youth age 6-17 reported wanting characters in books who they want “to be like” and who are “similar to me.” Fifty-percent of youth age 9-17 who read frequently also reported it is very or extremely important to them to include diversity—people and experiences different from their own.

Diversity in children’s books is not just a response to a rise in socially-conscious parenting. Children themselves yearn to be represented. Click To TweetBeyond character diversity we must also ask, who is writing our literature? Most of these books featuring underrepresented identities are written by people who themselves hold those identities or share similar experiences. Decades ago, these authors were children like me, also void of stories that resonated deeply with their own lives, confused about whether the life they lived at home was “normal,” or was respected enough to be celebrated and talked about. For decades, American literature has been lacking positive stories about underrepresented identities, but this is changing, and we need to elevate these new voices in children’s literature.

Diverse children’s books prompt kids to ask, “Who’s in my world?” When supplemented with diverse representation, the curiosity and desire to explore that youth naturally possess paves the path toward not only practicing inclusive behaviors at a young age, but also empowering youth to achieve their dreams and be proud of the identities they hold, the families they are a part of, and the communities that make them who they are. In turn, these early experiences become something they take with them as they grow—something my peers and I were bereft of as young readers.

When supplemented with diverse representation, the curiosity and desire to explore that youth naturally possess paves the path toward not only practicing inclusive behaviors at a young age. Click To TweetI am so inspired by the strides I have observed towards inclusion in children’s literature. As the next generation of caregivers, parents, teachers, and role models to youth, we need to take an active and conscious role in making sure these numbers don’t stay stagnant or become a literary fad. We must strive to achieve a more equitable representation of not just characters and stories but also authors and publishers. Checking out or purchasing from a “POC authors” shelf or “[insert race] history month” display may seem insignificant at first, but this intentional action does wonders to activate and inspire diverse authors and stories. Hopefully, we can one day walk into any bookstore or library and see what I saw last weekend become the new “normal”—for the next generation of bookworms and beyond.

As the next generation of caregivers, parents, teachers, and role models to youth, we need to take an active and conscious role in making sure these numbers don’t stay stagnant or become a literary fad. Click To TweetNote: Looking for a place to start? Here is a list of books written by diverse authors, telling stories about diverse experiences and the importance of inclusivity for children!