I’ve been reading the book, Creating Capabilities by Martha Nussbaum, a leading philosopher who writes about ethical ways to think about economic development. Her basic argument is that the GDP (Gross Domestic Product), the quantitative measure used to judge a nation’s level of economic health, largely misses what is most important about the health of a nation and its citizens. Instead, she describes the “Human Development Approach”, which is much more holistic and takes into account all of the diverse aspects that make both individuals and nations healthy and thrive. Although Nussbaum is writing mostly for ethicists, economists and political leaders, I think the Human Development Approach is relevant for many organizations, and especially those of us invested in diversity and inclusion. In many ways, she is writing about the advantages and disadvantages of counting versus caring.

As Nussbaum argues, there are lots of advantages to counting things—like demographics, changes in representation and economic growth. But measurements like the GDP, which calculates such a vast number like a nation’s average standard of living, can naturally overlook many human elements of health that are not so easily quantified. The Human Development Approach, which she proposes, focuses instead on things like length of lifespan, amount of leisure time, political freedom, bodily health and nutrition, creative avenues for imagination and reflection, and the ability to participate in social groups. All of these factors, she says, are elements that make up a truly healthy and holistic human life—and nation. But these are also aspects of life that can be more challenging to count, and therefore overlooked when categorizing a nation as “developed” or “developing.” This is how the US for example, is typically labeled a “developed” or “first world” country despite having significant populations living in extreme poverty. Or how so called “developing” or “third world” countries, which rank lower on the GDP, simultaneously have high degrees of political participation, social life and creative industries.

Of course the GDP is a useful metric for getting an idea of a nation’s baseline economic development. But its not very useful at painting a holistic picture of what makes a nation, and its people, diverse, healthy, and vibrant. In the same way, organizations, like schools and businesses, that rely on narrow metrics to keep up with the health and vibrancy of their education or inclusion levels can miss-out or mislead themselves by making the numbers say more than they should. I think this is largely a natural human tendency. Numbers are easy to grasp, they’re clear, efficient, and representative. So the challenge is to count things that can be counted, while caring for the things that elude quantification.

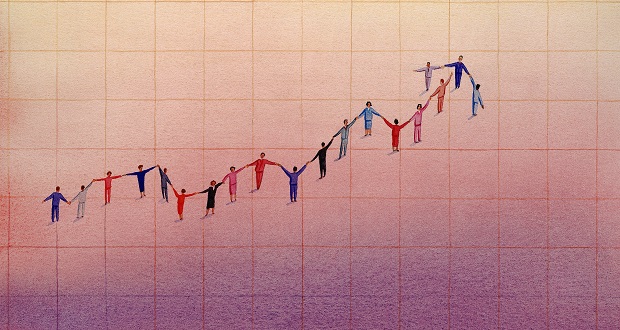

In diversity and inclusion work, it is important to make the distinction between our calculations of diversity scores, demographic changes, and inclusion metrics and the very human elements that live and breath behind the numbers—and the ones that never make the charts.

Nussbaum offers a helpful list of central capabilities of human flourishing which are relevant to the work of creating more inclusive people and cultures. Capabilities like play and creativity, when cultivated and encouraged, are vital to feeling included and free to be oneself at work. And its important to note that thinking more holistically about human beings and cultures does not mean doing away with our numbers and counting. It’s just the opposite. Numbers can be helpful starting places and symbols pointing to the more complex realities of organizational life. An organization, for example, may have some impressive numbers of increased women in leadership or veterans in the workforce. But the numbers should be used to ask the much deeper question about how these workers are being equipped to express themselves in all of their diverse and creative ways. In other words, the issue is not counting versus caring; but counting in order to care. Quantified measures become signposts that guide us along the journey of inclusion—and not just tempting comfortable stops along the way.